What we do know is that by 3000 BC several types of onions were grown in gardens, and writing on one ancient Egyptian pyramid wall even complained about the expense of providing slaves with onions and garlic! Other sources suggest Egyptian priests looked at the onion as a symbol of the universe with its round shape and the layers of the onion symbolizing the layers of heaven, earth and hell. In fact, onions are pictured on more pyramid tombs than any other plant!

|

| Onions were even used in the creation of mummies in ancient Egypt. |

Of course, the first thing most people think of when they think of onions is the aroma, which originates from an ail within the plant and escapes into the air as an irritating vapor when the onion is peeled or cut.

| The release of oil from inside the onion is what brings tears to your eyes! |

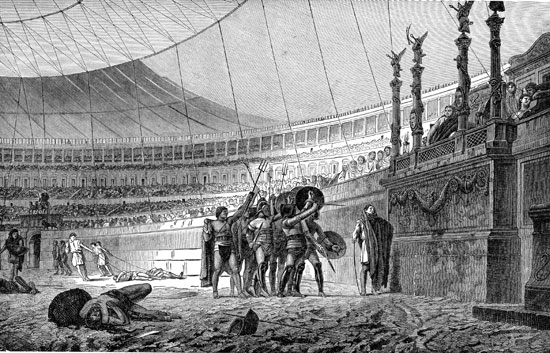

Early people thought onions with stronger scents had more power. In fact, early Romans often ate breakfasts of raw onions on bread, and Roman gladiators were often rubbed with onion juice to make them strong. Even Greeks in training for the early Olympics were told to eat 2 onions a day to make them strong.

|

| Gladiators like these ate onions and rubbed their bodies with the oil from onions to improve their strength. |

In North America, wild (meadow) onions grew long before the arrival of settlers, and Native Americans ate them raw after dipping them in salted water and dried them for food use during the winter. The first large yellow onions came over on the Mayflower in 1620, and they were a staple in Colonial gardens. Our nation's first president George Washington even said they were his favorite food!

|

| George's favorite food? Onions! |

- 3 large onions (you may want to try 3 different varieties—some are easier to grow than others)

- 3 jars/drinking glasses large enough to hold each onion without it rolling over

- water

Simple put the onion in each had with the rounded side down and add enough water to wet the bottom of the onion. Don't use too much water or your onion may rot. Then just put your jar in a bright area with plenty of light.

Within a week or so, you should see white roots coming from the bottom of the onion. A week or two later and you should start to see long green leaves coming from the top of the onion. The food for the leaves is being supplied by the bulb of the onion. Just make sure to keep enough water in the jar to cover the bottom of the onion.

When the leaves get about 4 inches tall, have an adult cut open the onion to see how the leaves have grown from the center of the bulb.

For a special treat, cook your onion in a dish for everyone to enjoy!